Cecil Sharp

One of the most important collector to travel to the area was British scholar and folksong collector Cecil Sharp who arrived in Madison County in 1916. He had already established himself as the person who was given the credit for preserving many of England’s traditional dances and music before traveling to the southern mountains of the United States.

A correspondence with Olive Campbell who had already traveled throughout the area collecting music prompted this trip. By the time she met Sharp, Mrs Campbell had collected over two hundred songs and ballads. The movie “Songcatcher” is loosely based on that endeavor. Sharp and his assistant Maud Karpeles traveled back into the hills of Madison County and took down the ballads to preserve those that had been passed down to the inhabitants of the more remote parts of the region from their British and Scottish ancestors. Sharp described some communities in the Blue Ridge as places where “singing is as common and almost as universal a practice as speaking.”

There is one other point to consider – the very democratic spirit of the people, which is, I imagine, rather more independent than that of English people of the same class – although, frankly, I know little of the English people. The mountain people are sensitive, proud and shy but will do things for you if they like you and feel that you like them.

–Sharp correspondence, letter from Mrs Campbell, 4.9.15

Sharp was driven into Madison County in July of 1916. One of the areas in the Laurel Country was a very remote section known then as Allanstand (the name Allanstand based on the fact that it was on a pack-horse route where the animals could ‘stand’ overnight, probably at a lodging originally owned or run by a person called Allen). One of the younger residents, Berzilla Chandler Wallin remembers that the people were nervous at first because they thought that he was surveying for a site for a new dam and they might lose their land. Their feelings softened and within four days Sharp had collected over fifty songs and had doubled this figure within seventeen days. In fact, Ziporah Rice, an aunt of Berzilla’s (known to all as “Aunt Zip”) was one of those who sang for Sharp.

Sharp spent four weeks in Madison County and we know from his diary that he was often driven around by Mitchell Wallin, Lee’s uncle, who played the fiddle for Sharp. According to Sharp’s diary, Mitchell Wallin was “a bad singer and a very difficult fiddler to note from” but Wallin is remembered by those in the area as a good fiddler. Mitchell’s half-sister, Mary Bullman Sands, sang 25 “love songs” (as ballads were called). Although Sharp was looking for songs, he also collected instrumental music. Reuben Hensley, father of thirteen year old Emma Hensley who gave Sharp a good version of the ballad Barbara Allen, played Sharp such tunes as Cumberland Gap. His travels in the county were published in a small booklet entitled Ballad Hunting in the Appalachians which included four letters he wrote during that summer. Sharp kept a diary and took photographs during his travels.

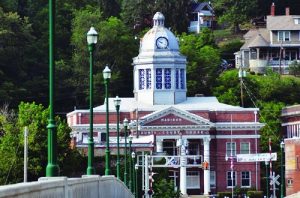

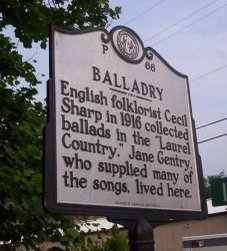

Cecil Sharp also went to Hot Springs, where he collected 70 songs from a single woman–Jane Hicks Gentry–the most he had collected from a single person. When Sharp’s English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians was published in 1932, it included forty songs given by Jane Gentry and additional songs from Madison County ballad singers whose family names are known today for their songs and tunes: the Wallins, Chandlers, Nortons, Rays, Sheltons and Ramseys. When he finally moved on to another area, Cecil Sharp had collected songs from thirty nine Madison County singers. Almost all of the Laurel area singers were descendants of Roderick Shelton. Indeed, of the “thirty nine Madison County singers that sang to Sharp, no less than twenty eight were related to this person.” In all, Cecil Sharp collected a total of 260 tunes in Madison County, NC. 158 of these were collected in one small area, comprising the settlements of White Rock, Alleghany, Allenstand, Carmen, Big Laurel, Rice Cove and Spillcorn. The remaining 102 songs came from the small town of Hot Springs (these include the 70 songs which came from Jane Gentry).